by Benedict Wachira

‘The UK is the largest European foreign investor in Kenya. Currently, there are about 100 British investment companies based in Kenya, valued at more than STG £2.0 billion.’

~Website of the British High Commission in Kenya

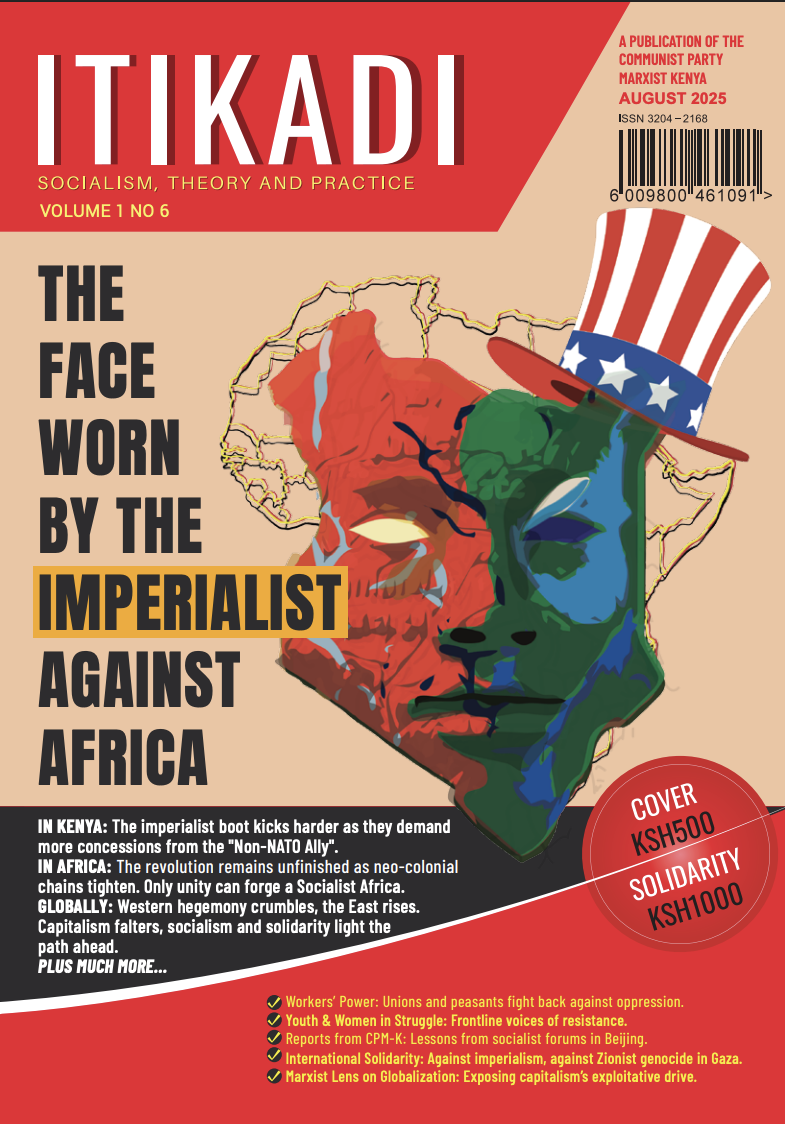

Title: Neo-colonialism - The last stage of imperialism

Author: Kwame Nkrumah

1 Introduction

There is no doubt that Kwame Nkrumah’s Neo-colonialism - The last stage of imperialism is extremely relevant in the Africa of today. Written in 1965, the analysis in the book can still be seen to different degrees in all African countries. The book extends Vladimir Lenin’s fundamental contributions to Marxism as found in his book ‘Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism’ by correctly analysing imperialism in the African context (even though Nkrumah was at the time still on his journey towards Marxism. [1])

The analysis in this article is limited to the introduction section in Nkrumah’s book, and it will focus on the relevance of the book’s analysis on Kenya.

Kenya’s economy is essentially neo-colonial. As Nkrumah explains, independence from colonialism paved way for indirect control by the former colonial master, Britain, and also by the rising imperialist power, the United States of America (USA) among other European imperialist powers. The article will highlight the neo-colonial stranglehold in Kenya by briefly focusing on agriculture, banking, trade, and the security sectors.

Before I proceed to contextualise neo-colonialism in Kenya today, I have to point out one issue in Nkrumah's analysis that was not relevant in the Africa of 1965 and is still not relevant today. Nkrumah contradicts himself by seeing the policy of non-alignment as an antithesis and cure to neo-colonialism. He posits that:

The struggle against neo-colonialism is not aimed at excluding the capital of the developed world from operating in less developed countries. It is aimed at preventing the financial power of the developed countries from being used in such a way as to impoverish the less developed…He [the capitalist country] may do better for himself if he invests in a non-aligned country than if he invests in a neo-colonial one.

He proceeds to argue that the ideological orientation of the financial power doesn't matter, as long as the non-aligned country pursues an independent national plan. What he later mentions but fails to apply in his analysis is that imperialism is a logical and historical result of capitalism, and as he correctly puts it, neo-colonialism is an expression of imperialism. It is therefore illogical (or perhaps opportunist) for him to claim that the so-called non-aligned countries can accept finance capital from capitalist/imperialist countries, but still somehow escape the manacles of neo-colonialism. Such an argument defeats the whole essence of his book.

2 Agriculture

Tea farming was introduced in Kenya in the colonial era and has since independence continued to be Kenya's leading export crop and one of the highest contributors to the country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP).[2] Kenya is Africa’s largest exporter of tea.[3] In 1982, almost 20 years after independence, Willy Mutunga noted that the British multinational, Brooke Bond,[4] which had monopolised both worldwide tea production and the world tea market controlled a significant portion of Kenya’s tea sector, to the detriment of the Kenyan nationals.[5] Today, Unilever (Brooke Bond's mother company) owns 16,223-acre tea farms and produces over 32 million kilogrammes of tea annually.[6] Finlays, founded over 200 years by Scotland's leading capitalist James Finlay and now owned by Britain's multinational John Swire & Sons Limited, is an affiliate of the Sun Capital Partners Company, an American multinational private equity firm[7] that owns 10,300 acres of tea farms. It produces over 28 million kilogrammes of tea per year.[8] Another British multinational company, Williamson Tea Company[9] farms tea on its 5,255-acre land in Kenya. In its financial year ending 2020, it sold over 15 million kilogrammes of tea and made a profit of over 4.8 million dollars.[10]

These three multinational entities, which control close to 20% of Kenya’s 450 000 tonnes annual tea production (without including their effective control of the sector) were established in Kenya during the colonial era (Unilever Tea Kenya Limited was established in 1922,[11] Williamson Tea in 1952[12] and Finlays close to 100 years ago[13]) and their structure of business continued uninterrupted even after independence. Kenyans who live close to the farms of the three multinational companies have historically accused the multinationals of having stolen their ancestral land, and currently, there is ongoing action in the National Land Commission where the locals are pushing for the non-extension of their hundred-year leases which are now in the final period towards expiry.[14] These three multinationals are a small representation of many other multinational companies that control the Kenyan agricultural sector, including coffee farming, horticulture, and fruit farming. Most of the profits are repatriated back to the mother countries to the detriment of neo-colonial Kenya.

3 Banking and Finance

According to the British High Commission in Kenya, ‘there are about 100 British investment companies based in Kenya, valued at more than STG £2.0 billion… Significant British investors include Barclays Bank, Standard Chartered Bank, GlaxoSmithKline, ACTIS (formerly CDC Capital Partners), De La Rue and Unilever.’[15]

De La Rue has been printing currency in Kenya since independence save for the period between 1966 and 1985 when another UK firm, Bradbury Wilkinson, did the job.[16] It currently has an annual money printing tender of 100 million dollars.[17]

In Kenya, the biggest banks owned by western interests are ABSA Bank, Standard Chartered, and Diamond Trust Bank. London-based Standard Chartered Bank PLC owns 73.89% of Kenya's Standard Bank Limited through its subsidiary, Standard Chartered Holdings (International) BV.[18] ABSA Bank Kenya PLC is owned by foreign shareholders who include Barclays Bank PLC (British owned), through their subsidiary ABSA group Limited which owns 68.5% of the Bank.[19] Diamond Trust Bank is controlled by the Aga Khan, who is a British citizen with vast international finance capital interests.[20] The three British-owned banks are part of the ten most profitable banks in Kenya, and they exert significant influence in the Kenyan financial scene, just as is expected of institutions of promotion of international finance capital. All three banks were established in Kenya during the colonial period.

4 Trade

Lenin argues that the rise of capitalist monopolies and combinations in the capitalist countries led to the scramble for raw materials in the underdeveloped territories, and also led to the search for new markets in those new territories.[21] This 'search' led to colonisation of Africa, which was seen as a source of cheap raw material, and as a place where international finance capital could be invested in return for more profits. This relationship continues today under neo-colonialism. Kenya continues to export unprocessed agricultural goods, and in return, imports finished industrial goods. In 2019, Kenya had a trade deficit of over 11 billion dollars.[22] In that year, raw exports, including horticulture, tea, coffee, and iron and steel accounted for 59% of the total export bills.[23] On the other hand, major imports including 'petroleum products, industrial machinery, iron and steel, motor vehicles, plastics in primary and non-primary form, and pharmaceutical products accounted for 49.5% of all import bills.[24] The neo-colonial nature of this form of trade is underlined by what is published in the United Kingdom High Commission in Kenya website[25] which states that:

The UK is Kenya's second most important export destination. Kenya mainly exports tea, coffee, and horticultural products, with the country accounting for 27% of the fresh produce and 56% of the black tea market in the UK. On the other hand, motor vehicles, printed materials, machinery, and chemicals form the bulk of imports from the United Kingdom.

The prices of the export goods are determined by the world markets, which is a euphemism for traders from the industrialised world, while Kenya and indeed Africa has no say on the price of the finished goods that it imports. Nkrumah noted this aspect of imperialism over 50 years ago and it continues to date.

5 Neo-colonial military presence in Kenya

In addition to the indirect economic and financial control of a neo-colonial state by external powers, Nkrumah states that ‘in an extreme case the troops of the imperial power may garrison the territory of the neo-colonial State and control the government of it.’ Even though Kenya does not currently fall within this extreme case, it is important to note that every year, over 10,000 British army troops perform their military training right in the middle of Kenya (Nanyuki).[26] This huge number of imperialist forces is extremely dangerous especially when it is compared to Kenya’s military personnel which stands at about 25,000 in number.[27] Given that the British troops have better equipment, long fighting history, probably better training, and a good knowledge of the Kenyan terrain, it is not far-fetched to imagine that the former colonial master may in an 'extreme case' use those troops to control the political and economic processes in Kenya. Indeed, in March this year, the British troops burnt over 10,000 acres of wildlife land during their training sessions, and not a single senior Kenyan government official publicly condemned the act.[28] This is in spite of the fact that Kenya depends heavily on wildlife tourism for her foreign exchange. The silence is an indication of the neo-colonial influence of the British in Kenya.

6 Conclusion

This article has shown, by use of Kenya as an example, that the analysis in Kwame Nkrumah’s Neo-colonialism - The last stage of imperialism is as relevant today as ever before. Beyond the weakness that this article pointed out at the beginning, it will be critical that Africa's present generations consult Nkrumah's wisdom, and chart a future for a Continent that is united, truly independent, anti-imperialist, and as Nkrumah later learned, socialist.

[1] Walter Rodney ‘Marxism and African Liberation’ 1975 https://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/rodney-walter/works/marxismandafrica.htm (accessed 21 April 2021).

[2] Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Economic Survey 2020 (2020) 94.

[3] Institute of Developing Economies ‘Unilever Tea Kenya (UTKL)’ https://www.ide.go.jp/English/Data/Africa_file/Company/kenya06.html (accessed 21 April 2021).

[4] Now owned by the British multinational company, Unilever PLC.

[5] W Mutunga ‘Finance Capital and the So-Called National Bourgeoisie in Kenya’ (1982) 12 Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies 61.

[6] n 5 above.

[7] Finlays ‘Finlays agrees sale terms of Horticulture Division with Sun European Partners’ 13 October 2015 https://www.swire.com/en/news/_press-releases/p151013.pdf (accessed 21 April 2021).

[8] Finlays ‘James Finlay Kenya - A Leading Producer and Supplier of Kenyan Tea’ https://www.finlays.net/about-us/locations/kenya/ (accessed 21 April 2021).

[9] Tea and Culture ‘History of Williamson Tea (Formerly Williamson&Magor)’ https://blog.teadog.com/2008/06/10/history-of-williamson-tea-formerly-williamsonmagor/#:~:text=Williamson%20Tea%20has%20been%20growing,Great%20Eastern%20Hotel%20in%20Calcutta. (accessed 21 April 2021).

[10] Williamson Tea Kenya PLC ‘Annual Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31st March 2020’ 16 July 2020 https://www.williamsontea.com/app/uploads/2020/07/Williamson-Tea-Kenya-Plc-Consolidated-Financial-Statements-for-the-year-ended-31st-March-2020.pdf (accessed 21 April 2021).

[11] n 5 above.

[12] George Williamson Kenya Limited ‘Report & Accounts 1996’ 20 June 1996 https://www.cmarcp.or.ke/index.php/agricultural/williamson-tea-kenya-ltd/361-1996-1/file (accessed 21 April 2021).

[13] n 10 above.

[14] Fresh Cup Magazine 'Unilever and James Finlay Forced off Kenyan Tea Farming Lands 13 March 2019' https://www.freshcup.com/unilever-and-james-finlay-forced-off-kenyan-tea-farming-lands/ (accessed 21 April 2021).

[15] British High Commission in Kenya ‘Trade & Investment’ https://www.kenyahighcom.org.uk/kenya-uk-relations (accessed 21 April 2021).

[16] Business Daily ‘De La Rue wins battle for Sh10bn-a-year Kenya currency printing contract’ 28 October 2018 https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/markets/marketnews/De-La-Rue-wins-battle-for-new-Kenya-currency-deal/3815534-4803438-wv17f3z/index.html (accessed 21 April 2021).

[17] As above.

[18] ‘Shareholding structure’ https://av.sc.com/ke/content/docs/ke-sc-holdings-international-bv-shareholding-structure.pdf (accessed 21 April 2021).

[19] ABSA Bank ‘Absa Bank Kenya PLC Shareholding structure.’ https://www.absabank.co.ke/content/dam/kenya/absa/pdf/Investor-Relations/Shareholding-structure/absa-bank-shareholding-structure.pdf (Accessed 21 April 2021).

[20] Juliet Atellah ‘who owns Kenyan banks?’ https://www.theelephant.info/data-stories/2019/08/16/who-owns-kenyan-banks/?print=pdf (accessed 21 April 2021).

[21] VI Lenin Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism 1963.

[22] n 3 above (94).

Excluding export apparel and clothing which is included in the percentage.

[23] As above.

[24] As above.

[25] https://www.kenyahighcom.org.uk/kenya-uk-relations (accessed 21 April 2021).

[26] BBC ‘Kenya arrests intruders in UK army camp 'break-in' attempt’ 6 January 2020 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-51006861 (accessed 21 April 2021).

[27] Business Daily ‘Kenya tops region’s military ranking’ May 18 2017 https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/news/Kenya-ranked-East-Africa-most-powerful-military-force/539546-3931860-6qk5e3/index.html (accessed 21 April 2021).

[28] The Sun ‘SAFARI FIRE Bungling British troops spark 10,000-acre wildfire on a nature reserve in Kenya home to elephants and lions’ 25 March 2021 https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/14459767/british-troops-spark-10000-acre-wildfire-reserve-kenya/ (accessed 21 April 2021).